Strength of the foundation

Writer Ben M. Freeman’s extraordinary new book “The Jews: An Indigenous People” demands that the world acknowledge who the Jews are, where we came from, and where we are going.

Review of “The Jews: An Indigenous People” by Ben M. Freeman, No Pasaran Media, 2025

The current resurgence of global antisemitism, led mainly by progressive leftists and radical Muslims, is remarkable in many ways. But perhaps the most striking is the extent to which it is predicated on lies. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to say that it is lies. Without lies, today’s neo-antisemites could never engage in their absurd pretensions to moral rectitude, and one hopes a great many couldn’t live with themselves. In other words, without lies, neo-antisemitism as a movement could not possibly exist.

The most immense and audacious of these lies is a direct attack on history itself. The neo-antisemites almost universally assert with a straight face that the Jewish people do not exist, that we have no genuine connection to the Land of Israel, and that the entire Zionist movement is a hoax fabricated by imperialist powers and the Elders of Zion. That this is not merely untrue but self-evidently psychopathic is deemed irrelevant by the neo-antisemites and happily elided by a great many others.

What is most remarkable about this lie is that it is so obviously false to anyone with even a cursory knowledge of the Hebrew Bible, the works of ancient Greek and Roman historians, the writings of the early Christians, basic archeology, and indeed any unbiased account of the ancient Near East. The origin of the Jews is the most settled of historical questions. That is precisely why it is under attack.

In his extraordinary new book, The Jews: An Indigenous People, writer Ben M. Freeman sets out to destroy the big lie once and for all. To do so, Freeman explores both the Jewish people's indigenousness and the concept of indigenousness itself.

In doing so, Freeman is refreshingly uncompromising. Indeed, his book is not a defense of the indigenousness of the Jews. As he should, Freeman takes this indigenousness as a given. Instead, the book demands that the world acknowledge, recognize, and respect this indigenousness, as they would that of any other people.

Freeman is also writing for Jews, however, because many of us, for various reasons, remain ignorant or unaware of the subject. Indeed, I was surprised to discover that I myself was, to some extent, ignorant and unaware. Like many others, I had assumed that indigenousness was simply to be a member of a specific group of people that has resided in a particular land for an exceptionally long time without significant change.

However, by delving into the concept of indigenousness, various attempts to codify it in international law, the perspectives of numerous indigenous activists from around the world, and other sources, Freeman reveals that indigenousness is far more complex and encompassing than I had initially believed.

Indigenousness, Freeman states, does not require a member of a specific group to reside in the same land as their ancient ancestors. It does not demand that the group in question remain unchanged across the centuries. Instead, as Freeman puts it: “An indigenous people are a group whose collective identity began in one specific land, and it is in that land they remained rooted (either physically, spiritually or culturally).”

Freeman also highlights something crucial to the case of the Jews: Indigenousness is not arbitrarily negated by a person’s absence from their ancestral homeland. All indigenous peoples have Diasporas, and those Diasporas are as indigenous as those who have remained in their ancestral lands. What truly defines indigenousness is not mere presence, but rather the depth of the ancestral connection. This connection is maintained by the preservation of cultural, linguistic, religious, and other qualities that originated in the homeland and continue to the present day.

In this sense, the indigenousness of the Jewish people is absolute. Everything that defines us—from the Hebrew language and the Hebrew Bible to the rituals of Jewish life, the Jewish calendar, Jewish holidays, and so on—is deeply rooted in and/or created in the land of Israel. As Freeman puts it: “As Jews—even if we don’t realize it—we express our indigeneity all the time, from keeping kosher to visiting Israel to circumcising our sons. Our practices and customs connect us to our land and our history constantly.” This fact is obvious to anyone who has lived in Israel and observed that the Jewish holidays are carefully synchronized with the change of seasons and even the geography and climate of the land itself.

This does not imply that the Jewish Diaspora is irrelevant. Indeed, Freeman makes certain to note that it is essential: “While there were always Jews living in our land, and while Jews always returned home, we should value the efforts of our ancestors in exile. They were the ones who, despite being cut off from the life source that was the Land of Israel, kept this tiny collective alive. It is their commitment to Jewish life, Jewishness, and the Land of Israel that made modern Zionism possible. Were it not for their commitment, work, and effort, there would not have been a people to return home.”

In this context, I was reminded of something I was once told by a rabbi in Jerusalem. We were discussing the profound mystery surrounding the longevity of Judaism and the Jewish people. As many have noted, the numerous ancient civilizations that flourished in the world into which Judaism was born have all passed into history. Only Judaism and its people have survived. So, we are forced to ask: Why are we still here?

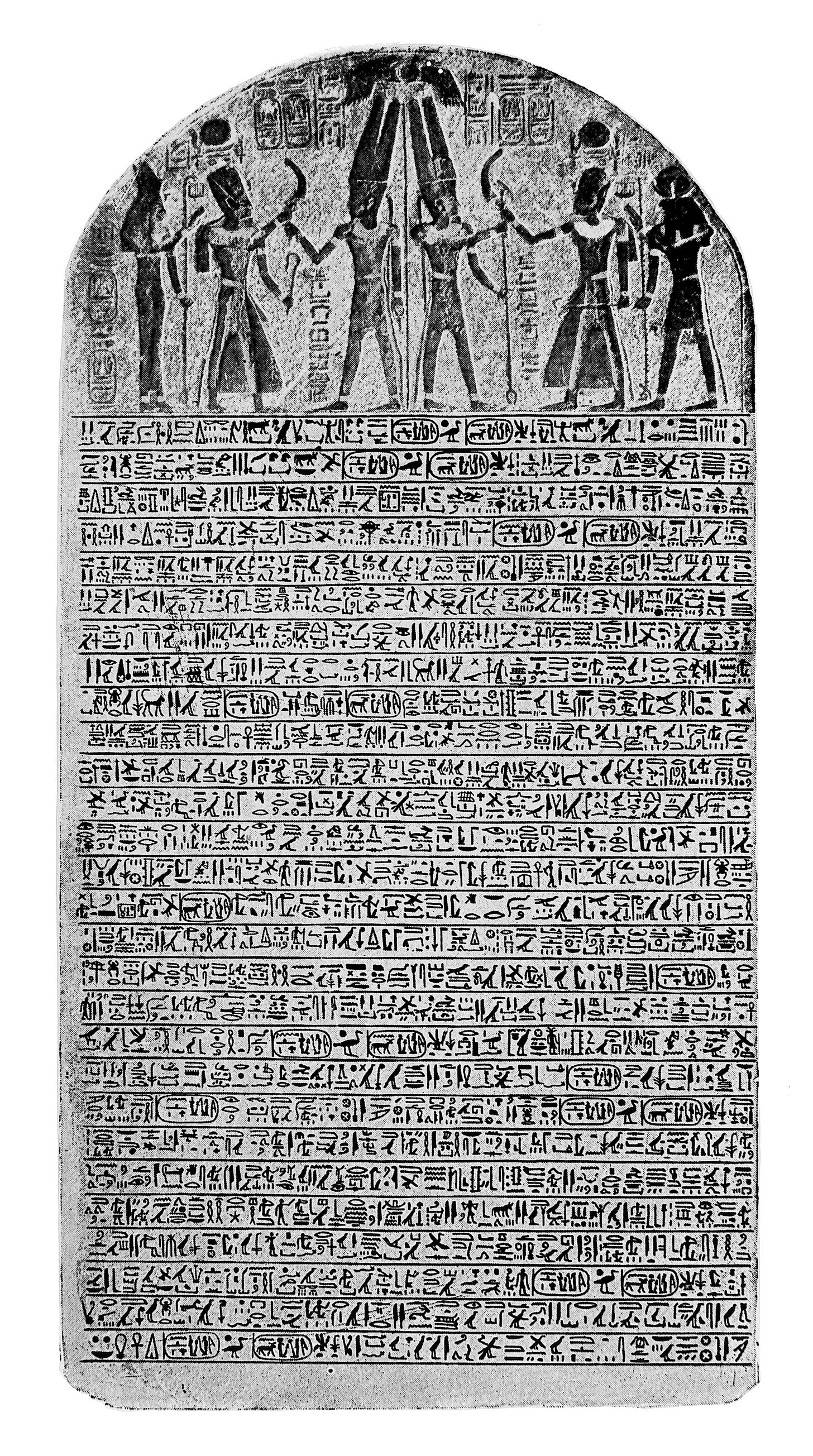

For me, the question is defined by a profound historical irony that subtly appears in Freeman’s book. Among the archeological finds that he cites in his survey of ancient Israel is the Merneptah Stele. This ancient stone monument dates from around 1200 BCE and lists the Egyptian Pharaoh Merneptah’s conquests across the Near East. Famously, it contains the first non-Jewish reference to a people called Israel residing in the Land of Israel. But the precise statement reads: “I have laid Israel low, her seed is not.” Thus, the first non-Jewish reference to the Jewish people is a declaration that we had ceased to exist. Yet today, Merneptah’s civilization is ruins and we are still here.

The rabbi told me that Jewish tradition explains this. He referred to it as “the strength of the foundation.” This principle holds that the foundation Abraham laid down for the Jewish people and Jewish life is so strong that it has endured everything the world has thrown at us for three millennia.

Freeman’s book is about this foundation. In effect, he is saying that the indigenousness of the Jewish people is our foundation. Our origins in our land, what we created there, and our connection to it have enabled the Jewish people to endure for such an exceptionally long time, regardless of our geographical location.

To his credit, Freeman also has a mission. He believes that the threat currently faced by the Jewish people is the gravest since the Holocaust. In this, he is undoubtedly correct. However, he does not seek to combat this neo-antisemitism just by asserting Jewish indigenousness but also by dispelling Jewish ignorance.

In the Diaspora, a significant number of Jews are tragically unaware of the strength of their own foundation. They recognize that the Jewish people were born in the Land of Israel. They are not deluded by claims that the Temple never existed or that the Jewish people are a fiction. Nor are they laboring under the delusion that the Palestinians are descended from the ancient Jebusites and Moabites, or any other such falsehoods.

But they still do not know that they are heirs to an extraordinary civilization born and built in the land that bears its name. “Indigenous groups today are the custodians of great and specific ideas, traditions, values and beliefs,” Freeman writes. “In our case, Jews today have inherited the great Jewish law, traditions, and the deep bond with the Land of Israel that originated over 3,000 years ago.”

Freeman wishes to remind Jews who may not know it of this essential fact. He wants to help them understand that indigenousness is not merely a statement of ownership. It is also a way of understanding ourselves because it is the only way we can fully understand who we are, where we came from, and where we are going.

As Freeman puts it: “As part of my work on Jewish Pride, I have always said that only Jews can and should define Jewish identity, and that non-Jewish definitions of what it means to be a Jew are illegitimate. I stand by this, but for Jews to define our identities, we must first understand and know our history and experience.” His goal, he writes, “is to enable all Jews to confidently say, ‘This is our story.’”

There’s no doubt that this is especially necessary in the United States, where the Reform movement has long been the largest Jewish denomination. While the Reform movement has its virtues, it has historically put a significant amount of energy into separating Jews from the Land of Israel and thus from their sense of indigenousness.

The Reform movement may have done this out of altruistic motives: It wanted to help Jews assimilate into the modern world. But regrettably, its legacy has left many young American Jews adrift, lacking a clear understanding of who they are.

In writing this book, Freeman is perhaps attempting to educate Jews, but “educate” implies something too prosaic. He is seeking to tell them who they are. He wants them to understand that the strength of the foundation lies not just in their connection to the Land of Israel or the State of Israel, but also to what was created in the Land of Israel and what the State of Israel is creating now. This is who they are, and it can tell them where they came from and where they are going.

The black American writer James Baldwin once asked an audience: “If one has got to prove one’s title to the land, isn’t four hundred years enough? Four hundred years? At least three wars? The American soil is full of the corpses of my ancestors. Why is my freedom or my citizenship, or my right to live there, how is it conceivably a question now?”

To the antisemites of today, we must ask: If one has got to prove one’s title to the land, isn't 3,000 years enough? Aren’t the millennia of sweat and blood the Jewish people have poured into that land enough? Isn’t the simple fact that we are still here enough?

Our enemies will say no, because they must say no. They have no other choice. Were they to say yes, they would disintegrate and expire of their own scorn.

In this book, Freeman offers to Jews, especially young Jews, the best answer to our enemies: Those who refuse to recognize our title to the land deserve it not for themselves. Thus, Freeman drives a stake through the heart of a monster that has already been indulged for far too long by a world that ought to know better. For this, we owe him a very great debt of thanks.