The Zinn protocols

Howard Zinn’s infamous “A People’s History of the United States” is the great proto-text of today’s neo-antisemitism.

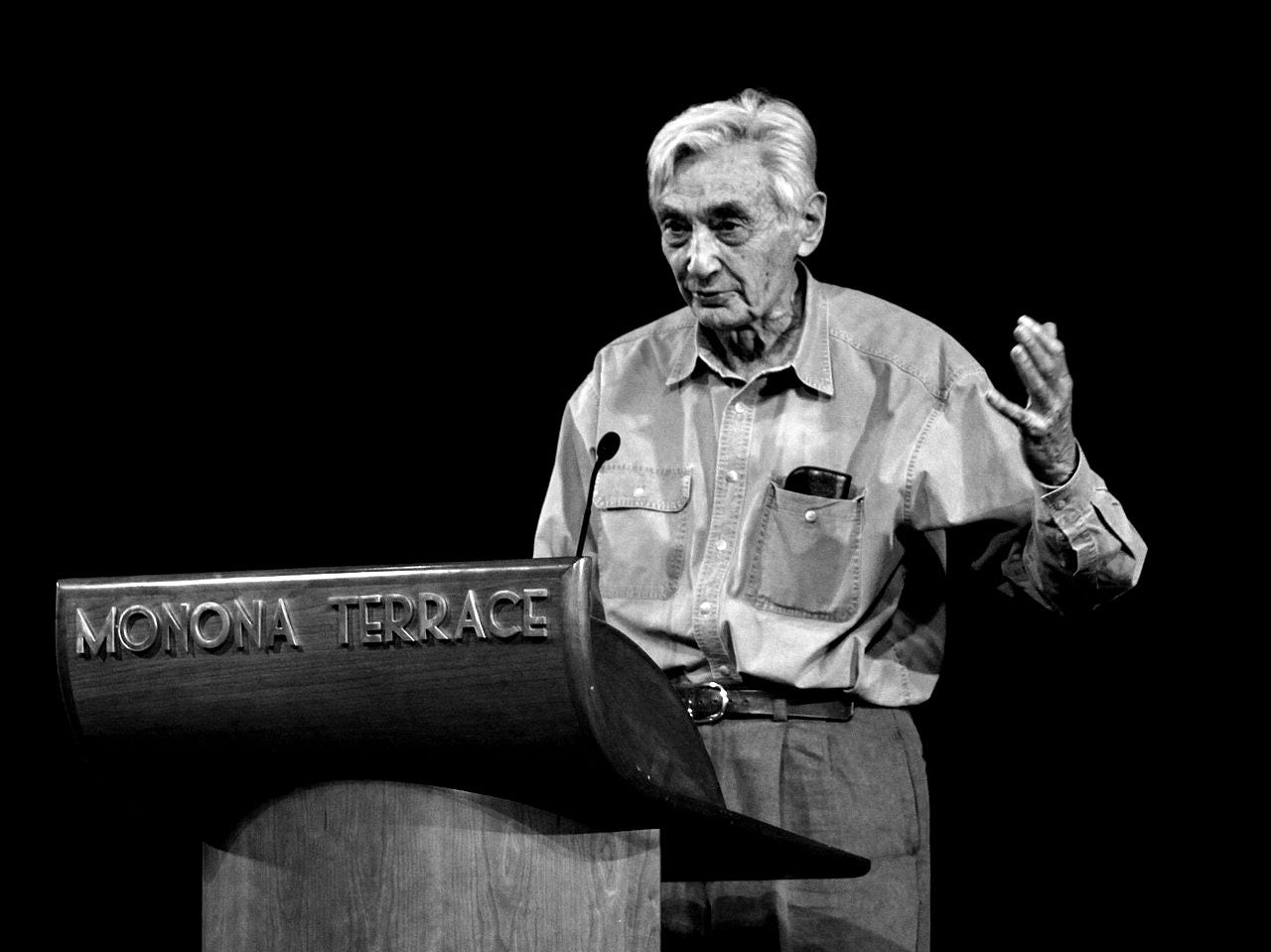

With the exception of Noam Chomsky, perhaps no intellectual has been more influential on today’s American neo-communists and radical progressives than Howard Zinn. The far-left academic, who died in 2010, literally wrote the book on the left’s revisionist history of the United States.

With his A People’s History of the United States, a bestseller thanks to generations of academics forcing their students to buy it, Zinn outlined a comprehensive vision of this history—likely drawn from Stalinist propaganda—that portrays the United States as a conspiratorial fraud got up by white racists and rapacious capitalists.

The conspirators, Zinn claims again and again over hundreds of pages, brutally exploit the American people, who are too duped or stupid to realize the truth of their plight. Thankfully, Zinn is there to enlighten them.

It is impossible to overestimate the power this vision exercises over today’s radical left. They have effectively adopted Zinn’s claims wholesale without the slightest question. Zinn’s influence is palpable in the tearing down of statues, demonization of the US as a racist and genocidal entity, and even “mainstream” efforts like the New York Times’ 1619 Project. If the radical left has a vision of what the US is, it is Zinn’s vision.

Among fans, A People’s History is something like a bible. They view it as a fearless act of speaking truth to power, in which the secret knowledge of the real history of the US is finally revealed. In turn, this revelation gives their lives purpose, meaning, and an ultimate goal: the overthrow of the conspiracy of Zinn’s imaginings.

One must feel a pang of sympathy for people so lost that such a book is enough to give them a sense of personal redemption. Nonetheless, A People’s History is very far from what they imagine.

If Zinn’s book is anything, it is a debased conspiracy theory based on a fundamentally paranoid worldview. Its historical method and distortions have been much criticized, for good reason. More important is its cumulative effect, which is to foster a cult of hatred and, at times, outright treason.

It is also, though little noted, a profoundly sinister work. It is, ultimately and perhaps unknowingly, rooted in classic antisemitic themes of an omnipotent, all-pervasive, and malicious conspiracy by a shadowy “elite”—a word Zinn repeats ad nauseum—against the beleaguered “people.” It is a very short step indeed from Zinn’s American “elite” to the Elders of Zion.

In this, A People’s History may be viewed as one of the primary sources of the left’s current descent into genocidal neo-antisemitism. The book may replace the Jews with an American “elite” and an American conspiracy, but its overall worldview is a way in, an access point to the most ancient antisemitic myths. The radical left has now seized upon those myths with everything it has.

In this, Zinn’s work is execrable, but also worth exploring, if only for the sake of understanding how we got here.

The killer elite

The essence of Zinn’s conspiracy theory is a kind of vulgarization of “elite theory” as formulated by Vilfredo Pareto, Robert Michels, James Burnham, and other 20th-century intellectuals.

Like “vulgar Marxists,” Zinn reduces this complex and challenging set of theories to a debased and simplistic view of the world as a Manichean battle between good and evil.

Zinn’s vulgarization of elite theory—which he punctuates, again, by endless repetition of the word “elite”—is typified by his concept of who or what his elite actually is. In effect, it is nothing at all. It serves as little more than an all-purpose bogeyman, endlessly shifting and vague. That is, Zinn’s elite is whatever he wants it to be at any given moment.

This is antithetical to the work of the elite theorists, who saw elites as inevitable, necessary, and certainly not monolithic. They believed society was a mosaic of elites, some serving the good and some not. They endlessly compete with and replace each other, and are often superseded by new elites of a very different kind.

Zinn, in contrast, presents the “elite” as nothing more than his villain of the moment, which is always the leaders of the United States. In Zinn’s vision, those who founded and formed the country did so in order to serve their own selfish interests and always work against the interests of an amorphous “people.” And like his “elite,” Zinn never really seeks to define “the people” except as another monolithic and ever-shifting entity.

In other words, Zinn posits that the United States is nothing more than a creation of the forces of evil and, therefore, an expression of evil itself. It is the devil loose in the world.

The revolutionary conspiracy

Contrary to Zinn’s constant claims that he was not a conspiracy theorist, with such statements as “it was not a conscious conspiracy, but an accumulation of tactical responses,” his “elite” is always conspiratorial in nature.

For example, early in the book, Zinn claims that the American Revolution was nothing more than a conspiracy to oppress more or less everyone.

He writes, “By the years of the Revolutionary crisis, the 1760s, the wealthy elite that controlled the British colonies on the American mainland had 150 years of experience, had learned certain things about how to rule. They had various fears, but also had developed tactics to deal with what they feared.”

Zinn, as good communists always do, sees this conspiracy as class-based. He states, “With the problem of Indian hostility, and the danger of slave revolts, the colonial elite had to consider the class anger of poor whites—servants, tenants, the city poor, the propertyless, the taxpayer, the soldier and sailor. … Better to make war on the Indian, gain the support of the white, divert possible class conflict by turning poor whites against Indians for the security of the elite.”

This conspiracy proved ineffective, however, so the “elite” got up the American Revolution as another level of control: “By this time also, there emerged, according to Jack Greene, ‘stable, coherent, effective and acknowledged local political and social elites.’ And by the 1760s, this local leadership saw the possibility of directing much of the rebellious energy against England and her local officials.”

“Perhaps once the British were out of the way, the Indians could be dealt with,” Zinn muses.

He then tells us that this was “no conscious forethought strategy by the colonial elite, but a growing awareness as events developed,” even though he has just claimed that it was a conscious forethought strategy.

The health of the state

The conspiracy that was the American Revolution was very effective: “The military conflict itself, by dominating everything in its time, diminished other issues, made people choose sides in the one contest that was publicly important, forced people onto the side of the Revolution whose interest in Independence was not at all obvious.”

In making this claim, Zinn resorts to one of the most redolent cliches of conspiracy theorists both left and right, saying, “Ruling elites seem to have learned through the generations—consciously or not—that war makes them more secure against internal trouble.”

It is important to note that this is nonsense. If anything, war often results in the destruction of the ruling elite.

For example, the democratic regime of ancient Athens died, for a time, as a result of the Peloponnesian War. In the modern era, the depredations of World War I resulted in the collapse of long-standing regimes in both Russia and Germany. In World War II, the French Third Republic and, eventually, Nazi Germany both fell. Russia’s war in Afghanistan contributed mightily to the collapse of the Soviet regime. We need not even mention the “internal trouble” that overtook the United States during the Vietnam War, to which Zinn himself contributed.

War, in other words, is very far from the health of the state.

Constitutional fraud

The Revolutionary War may have been a conspiracy, but in Zinn’s view, the truly triumphant conspiracy was the US Constitution. He claims: “The Constitution, then, illustrates the complexity of the American system: that it serves the interests of a wealthy elite, but also does enough for small property owners, for middle-income mechanics and farmers, to build a broad base of support.”

Brilliantly, the “elite” ensured that “The slightly prosperous people who make up this base of support are buffers against the blacks, the Indians, the very poor whites. They enable the elite to keep control with a minimum of coercion, a maximum of law—all made palatable by the fanfare of patriotism and unity.”

Zinn’s great contribution here is the endlessly repeated leftist talking point that the Constitution is illegitimate because it was formulated by rich white people.

He states, “It is pretended that, as in the Preamble to the Constitution, it is ‘we the people’ who wrote that document, rather than fifty-five privileged white males whose class interest required a strong central government.”

This fraud, Zinn claims, was infinite in its success. He asserts: “That use of government for class purposes, to serve the needs of the wealthy and powerful, has continued throughout American history, down to the present day. It is disguised by language that suggests all of us—rich and poor and middle class—have a common interest.”

The farce of civil war

The perpetual success of this fraud is shown by the fact that, in Zinn’s hands, it essentially defines every significant moment in American history.

He writes of abolitionism and the Civil War, for example, “Such a national government would never accept an end to slavery by rebellion. It would end slavery only under conditions controlled by whites, and only when required by the political and economic needs of the business elite of the North.”

Indeed, Abraham Lincoln himself was a fraud, with Zinn describing him as someone “who combined perfectly the needs of business, the political ambition of the new Republican party, and the rhetoric of humanitarianism. He would keep the abolition of slavery not at the top of his list of priorities, but close enough to the top so it could be pushed there temporarily by abolitionist pressures and by practical political advantage.”

Echoing pro-Confederate “lost cause” historiography, Zinn claims that the Civil War was “not over slavery as a moral institution—most northerners did not care enough about slavery to make sacrifices for it, certainly not the sacrifice of war. It was not a clash of peoples (most northern whites were not economically favored, not politically powerful; most southern whites were poor farmers, not decisionmakers) but of elites.”

The robber baron regime

Having won the war, Zinn’s “elite” then turned itself to the full-on oppression that would define modern America.

Zinn states, “In the year 1877, the signals were given for the rest of the century: the black would be put back; the strikes of white workers would not be tolerated; the industrial and political elites of North and South would take hold of the country and organize the greatest march of economic growth in human history.”

“They would do it with the aid of, and at the expense of, black labor, white labor, Chinese labor, European immigrant labor, female labor, rewarding them differently by race, sex, national origin, and social class, in such a way as to create separate levels of oppression—a skillful terracing to stabilize the pyramid of wealth,” he claims.

Thus, the conspirators built the United States we know today.

The non-people’s war

It would consume far too many pixels to encompass the entirety of Zinn’s list of elite depredations. Suffice it to say that he regards every major event in American history that people regard as even vaguely admirable as a fraud perpetrated to the elite’s malignant benefit.

This culminates, in many ways, in Zinn’s view of World War II. Perhaps surprisingly, as he was a veteran of that war, Zinn views even that conflict—one against absolute political evil—as a monstrous fraud.

He claims, like many right-wing opponents of the war, that it was all about money.

Zinn asserts: “It was a war waged by a government whose chief beneficiary—despite volumes of reforms—was a wealthy elite. The alliance between big business and the government went back to the very first proposals of Alexander Hamilton to Congress after the Revolutionary War. By World War II that partnership had developed and intensified. During the Depression, Roosevelt had once denounced the ‘economic royalists,’ but he always had the support of certain important business leaders. During the war, as Bruce Catton saw it from his post in the War Production Board: ‘The economic royalists, denounced and derided … had a part to play now.’”

Zinn emphasizes the elite nature of the war with a rather bizarre attempt to define what he calls a “people’s war,” stating, “So, there was a mass base of support for what became the heaviest bombardment of civilians ever undertaken in any war: the aerial attacks on German and Japanese cities. One might argue that this popular support made it a ‘people’s war.’ But if ‘people’s war’ means a war of people against attack, a defensive war—if it means a war fought for humane reasons instead of for the privileges of an elite, a war against the few, not the many—then the tactics of all-out aerial assault against the populations of Germany and Japan destroy that notion.”

We can put aside the debate over the aerial bombing of Axis cities, which is, to an extent, a legitimate one. Zinn’s point, after all, is not really about tactics but about definitions. In this, his claim is obviously fallacious. It is perfectly possible for a “people’s war” to be one that commands wide consensus among “the people.” Indeed, that is obviously what it is.

By contrast, the argument over defense or aggression is not over what constitutes a “people’s war.” It is over what constitutes a “just war.” There are numerous theories in this regard, but Zinn engages with none of them. He simply dismisses the war as yet another conflict got up to serve “the privileges of an elite.” In the case of a war against political evil, this has very dark implications indeed.

The almost-ultimate conspiracy theory

Zinn consolidates his conspiracy theory via the left-wing cliche of the “1%.” That is, the claim that a tiny economic and political minority brutally exploits everybody else.

“Against the reality of that desperate, bitter battle for resources made scarce by elite control, I am taking the liberty of uniting those 99 percent as ‘the people,’” he states. “I have been writing a history that attempts to represent their submerged, deflected, common interest. To emphasize the commonality of the 99 percent, to declare deep enmity of interest with the 1 percent, is to do exactly what the governments of the United States, and the wealthy elite allied to them—from the Founding Fathers to now—have tried their best to prevent.”

“With such continuing malaise,” Zinn claims, “it is very important for the Establishment—that uneasy club of business executives, generals, and politicos—to maintain the historic pretension of national unity, in which the government represents all the people, and the common enemy is overseas, not at home, where disasters of economics or war are unfortunate errors or tragic accidents, to be corrected by the members of the same club that brought the disasters.”

“It is important for them also to make sure this artificial unity of highly privileged and slightly privileged is the only unity—that the 99 percent remain split in countless ways, and turn against one another to vent their angers,” Zinn states.

In other words, far from being a confluence of many incommensurable and competing forces, the “people” is a monolithic, almost mythological entity, duped and exploited, who must realize they are one and fight back against their ostensible oppressors. The only obstacle to this is the conspiracy of the “elites,” which has somehow brainwashed “the people” into undermining themselves through disunity.

This is where Zinn fully reveals himself as a conspiracy theorist, because he openly states that all this is the result of a conscious plan by a malignant cabal: “How skillful to tax the middle class to pay for the relief of the poor, building resentment on top of humiliation! How adroit to bus poor black youngsters into poor white neighborhoods, in a violent exchange of impoverished schools, while the schools of the rich remain untouched and the wealth of the nation, doled out carefully where children need free milk, is drained for billion-dollar aircraft carriers.”

“How ingenious to meet the demands of blacks and women for equality by giving them small special benefits, and setting them in competition with everyone else for jobs made scarce by an irrational, wasteful system,” the cheap demagoguery continues. “How wise to turn the fear and anger of the majority toward a class of criminals bred—by economic inequity—faster than they can be put away, deflecting attention from the huge thefts of national resources carried out within the law by men in executive offices.”

This is many things. For example, it is obviously quite mad. But it is also the essence of conspiracy theory and, indeed, an evocation—likely unintentional—of the ultimate conspiracy theory, the greatest and most murderous of all.

Protocols

Zinn was of Jewish descent and, I imagine, not consciously antisemitic. His primary ideological source was probably Soviet Cold War anti-American propaganda. Nonetheless, his book is redolent with the spirit of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion.

This 19th-century fraud, perpetrated by the Czarist secret police, is essentially the mother of all 20th-century conspiracy theories, much beloved by the Nazis, Muslim supremacists, and today’s left- and right-wing racists. Indeed, a good section of the Hamas charter is a word-for-word copy/paste of the Protocols, with, of course, the word “Jew” replaced by “Zionist.”

I categorically refuse to quote the document, so suffice it to say that it claims to be a transcript of a meeting by a secret cabal of Jews who outline a global Jewish conspiracy of extraordinary scope. According to the forgery, the Jews are a force for worldwide omnipotent and omnipresent evil, controlling everything from politics to economics to culture in order to exploit, oppress, and destroy “the goyim.”

Even when placed in other contexts, the great themes of the Protocols remain in almost every conspiracy theory: the secret cabal, the few exploiting the many, the malignant omnipotence, the totality of the depredations, the monstrous nihilist motives of the conspirators, and above all, the necessity of breaching and destroying the conspiracy and, with it, the conspirators. The Protocols are, in the end, a writ of genocide.

A People’s History of the United States and Zinn’s vision as a whole are, essentially, the Protocols transferred to the context of American history. Zinn simply replaces the Jews with his sinister American “elite,” who plot and do everything the Elders of Zion plot and do.

In the Protocols, the victim is all non-Jews, while in A People’s History, it is the American people who, manipulated by the conspirators, are helpless subjects of exploitation and destruction. A People’s History is nothing more than the Protocols of the Elders of the United States.

Even if Zinn did not intend it, the horrendous repercussions of this should be obvious: By conveying the spirit of the Protocols to a new generation of leftists, he prompted his acolytes to grasp upon that spirit as their means of redemption. Eventually, they embraced not only that spirit but the source of that spirit.

Sooner or later, all conspiracy theories end with the Elders of Zion, and that is where the left has now ended up—with something very like a new crypto-Nazism.

In some ways, this should not be entirely surprising. Though it has been assiduously covered up, the left has a long tradition of antisemitism.

Proto-anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, for example, once wrote, “The Jew is the enemy of humankind. They must be sent back to Asia or be exterminated.”

Marx himself asserted, “The Jew is perpetually created by civil society from its own entrails” and “money is the jealous god of Israel, in face of which no other god may exist.” The ultimate guru of the left, in other words, believed that Jews were literal excrement.

Consciously or unconsciously, Zinn conveyed this spirit to a new generation. He gave that generation a way into antisemitism. He gave them permission to believe the world is a conspiracy and, though Zinn viewed this conspiracy as fundamentally American, his followers were always bound to “find” the Jew behind the curtain.

In other words, today’s neo-antisemitism—the work of neo-communists, radical progressives, and Muslim supremacists—is by no means new. A People’s History was its nexus and entry point. It is the great proto-text of neo-antisemitism. All of it is there in this windy and bulbous volume, barely disguised by anti-Americanism and classist demagoguery.

The book was, in the end, a kind of time bomb, a crypto-antisemitic explosive that would inevitably detonate and threaten not only American Jews but the American republic whose overthrow was the great task the book set before its worshippers.

No modern society, after all, can or has ever survived antisemitism, and perhaps this was the whole point. It may be that, by introducing antisemitism into the American mainstream, today’s radical left hopes to inject a slow poison into America’s veins. One that will finally bring down the monstrous edifice.

If anything is clear, it is that the auto-destructive goal of Zinn and his acolytes must be thwarted. The poison of neo-antisemitism must be purged by whatever legal and moral means necessary.

If it is not, then Zinn’s great ambition will be realized: The America he hated will pass from the earth, and not just the “elite” but “the people” he claimed to love will be in a very great deal of trouble indeed.

Perfect analysis of this communist menace. That this book is assigned in high schools demonstrates the extraordinary degree to which the Marxist left has taken over our institutions.

Thank you, Benjamin, for this important information and with its historical context. Although embarrassing to admit, I was unaware of this. As a friend of mine would occasionally say, "Well - that explains a lot!"